Concepts

Complete Output Variables → Consume Variables first, then come back to this article as a reference manual. We use 🌟 to highlight concepts worth mastering early.

Reading Path

- Skim the terminology navigator below to confirm the term you need is covered.

- Study the “Core Concepts” diagram to link variables, scopes, and AST into one picture.

- Jump to the sections you need based on the problem at hand—no need to read in order.

- Core Ideas

- AST Related

- ASTNode: Nodes in the AST tree, each describing a piece of variable information.

- ASTNodeJSON: The JSON serialization of an ASTNode.

- Declaration 🌟: Identifier + definition, the smallest information unit in the variable engine.

- Type 🌟: A definition that constrains the range of possible values for a variable.

- Expression: Consumes variables and produces a new one.

- Scope Relationships

- Scope Chain: Determines which other scopes a scope can read variables from.

- Dependency Scope: The upstream scopes whose outputs are readable here.

- Covering Scope: The downstream scopes that can read this scope’s outputs.

- Node Scope 🌟: The public variable set of a node.

- Node Private Scope: Variables only accessible to the node and its children.

- Global Scope: Shared variables readable from every scope.

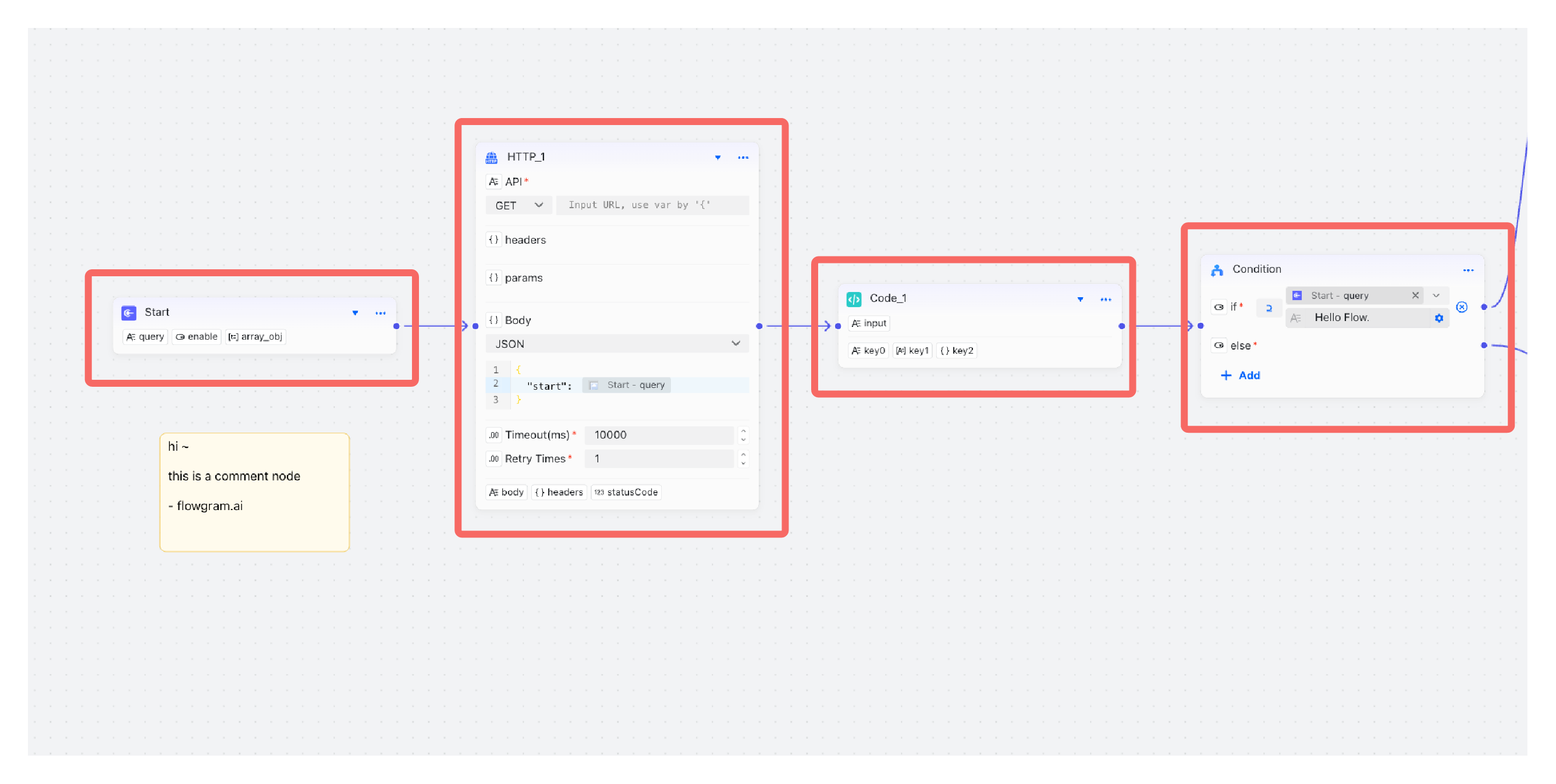

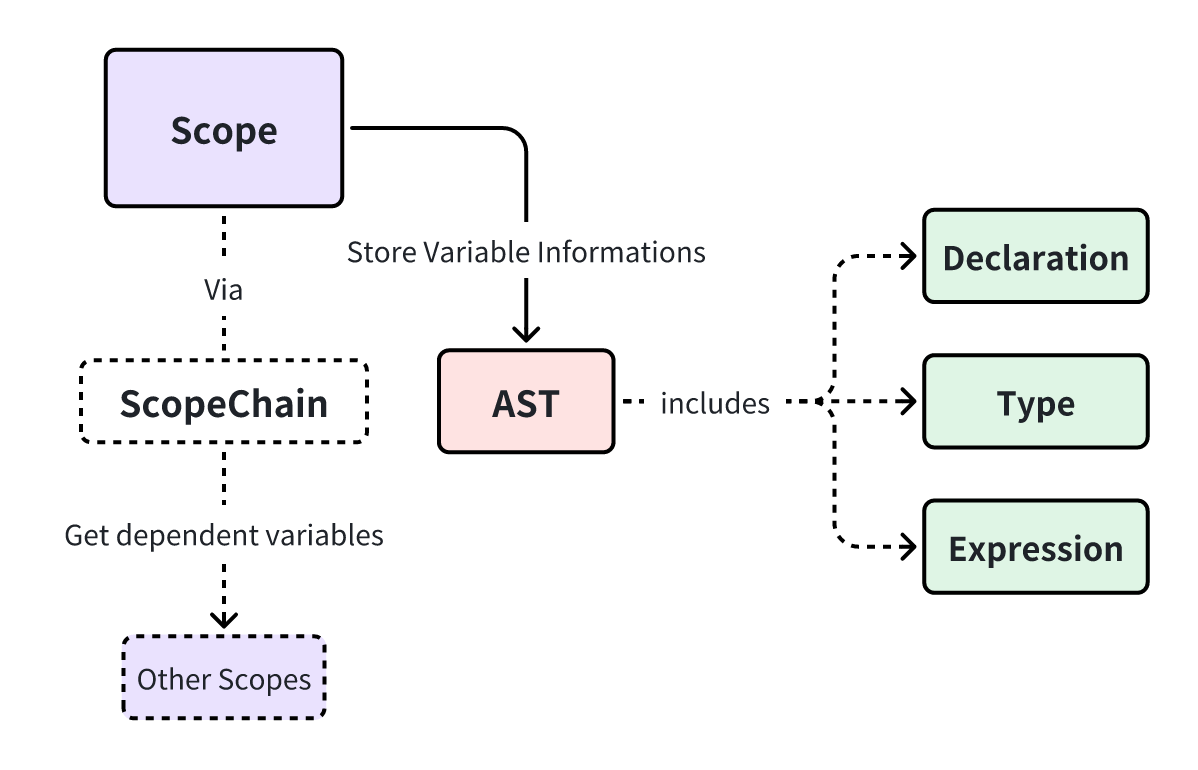

Core Concepts

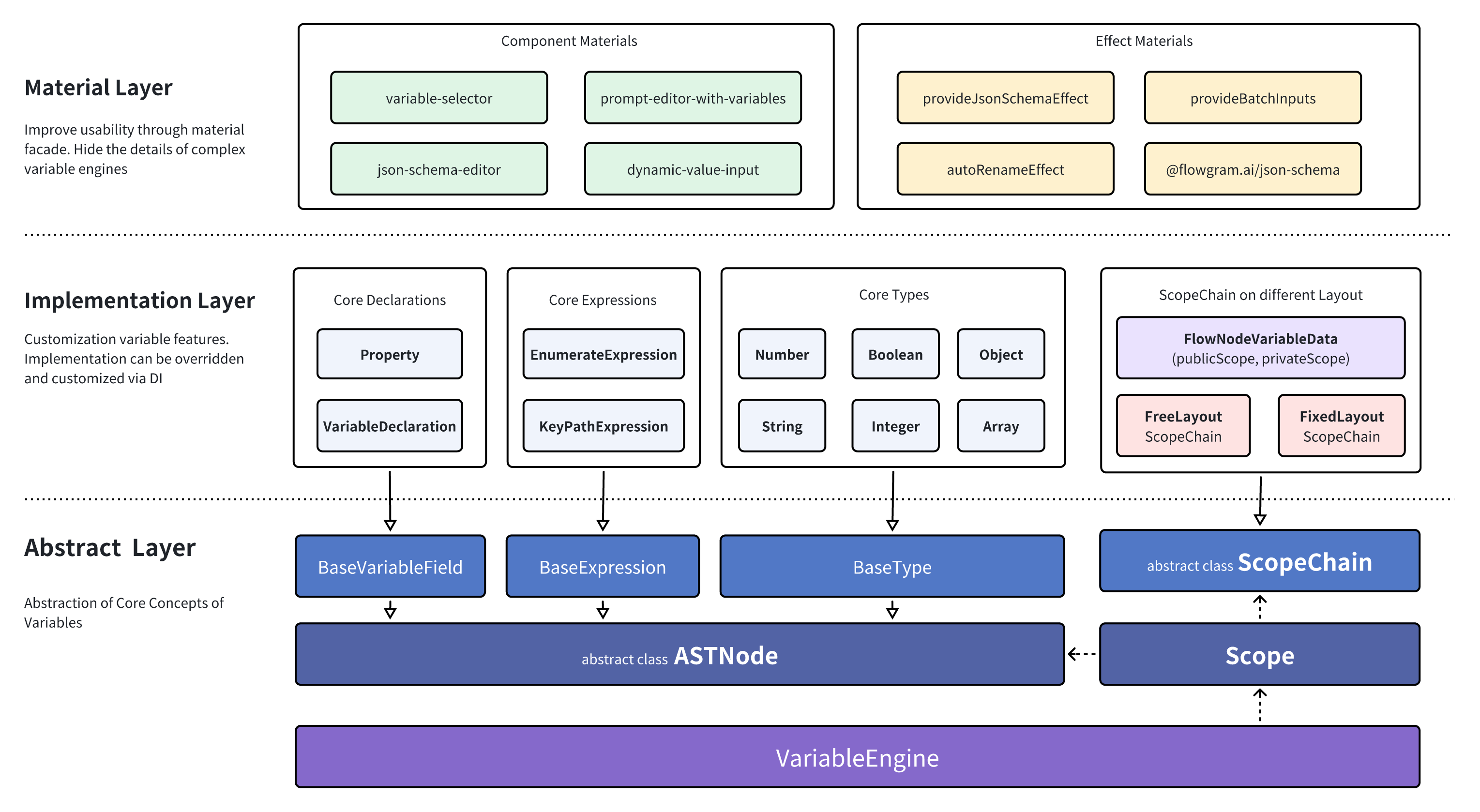

You can connect the variable engine’s core concepts through the diagram below:

- Green nodes represent what the information is, such as variables, types, or expressions.

- Red nodes represent how the information is stored, namely AST nodes.

- Purple nodes represent where the information lives, i.e., scopes.

- Dashed nodes and lines depict how the information flows, which is the scope chain.

To keep things tangible, hold on to one real-world case:

A “Batch” node reads the array output from an upstream HTTP node → iterates to produce

item→ and continues usingiteminside its child nodes.

Every concept mentioned in that workflow appears below, so feel free to cross-reference as you read.

Variable

Variables are containers defined during design time and evaluated during runtime. See Variable Introduction for a deeper primer.

In process design, variables only focus on definitions, not values. The value of a variable is dynamically calculated at the process's runtime.

Scope 🌟

A scope is a container that bundles variable information and keeps track of relationships with other scopes. In short, a scope decides “who can access which variables.”

Its boundaries vary by business scenario; the three most common cases are:

- Node ≠ scope: a single node may need both a public scope and a private one.

- Some scopes, like the global drawer, live outside of any node.

- Certain nodes require multiple layers of scopes (e.g., a loop’s private scope), which can’t be expressed with the node concept alone.

AST 🌟

Scopes store variable information through an AST. Treat it as a tree where each node describes a declaration, type, or expression.

Through scope.ast you can access the tree inside a scope and perform CRUD operations on variable information.

ASTNode

ASTNode is the basic information unit used in the variable engine to store variable information. It can model various pieces of information:

- Declarations: such as

VariableDeclaration, used to declare new variables. - Types: such as

StringType, used to represent the String type. - Expressions: such as

KeyPathExpression, used to reference variables.

- Tree Structure:

ASTNodecan be nested to form a tree (AST) to represent complex variable structures. - Serialization:

ASTNodecan be converted to and from JSON format (ASTNodeJSON) for storage or transmission. - Extensibility: New features can be added by extending the

ASTNodebase class. - Reactivity: Changes in

ASTNodevalues trigger events, enabling a reactive programming model.

ASTNodeJSON

ASTNodeJSON is the pure JSON serialization of an ASTNode. We usually construct it on the design side and let the variable engine instantiate it later.

Its most important field is kind, which indicates the type of the ASTNode:

When using the variable engine, we describe variable information with ASTNodeJSON. The engine then instantiates it into an ASTNode and stores it in the scope.

The relationship between ASTNodeJSON and ASTNode is similar to the relationship between JSX and VDOM in React.

ASTNodeJSONis instantiated intoASTNodeby the variable engine.JSXis instantiated intoVDOMby the React engine.

Json Schema is a format for describing the structure of JSON data:

Json Schemaonly describes the type information of a variable, whileASTNodeJSONcan also contain other information about the variable (e.g., its initial value).ASTNodeJSONcan be instantiated into anASTNodeby the variable engine, enabling capabilities like reactive listening.Json Schemais good at describing Json types, whileASTNodeJSONcan define more complex behaviors through custom extensions.

In terms of technical selection, the VariableEngine requires more powerful extension and expression capabilities. Therefore, ASTNodeJSON is needed to describe richer and more complex variable information, such as implementing dynamic type inference and automatic linking by defining the initial value of variables.

However, as an industry-standard format for describing JSON types, Json Schema has advantages in ease of use, cross-team communication, and ecosystem (e.g., ajv, zod). Therefore, we use Json Schema extensively in our Materials to lower the barrier to entry.

The variable engine provides ASTFactory for type-safe creation of ASTNodeJSON:

Declaration 🌟

Declaration = Identifier (Key) + Definition. In design mode, a declaration is an ASTNode that stores an identifier plus variable information—the smallest unit that can be referenced.

- Identifier (Key): The index used to access a declaration.

- Definition: The information carried by the declaration. For a variable, the definition = type + right-hand value.

Variable Declaration = Identifier + Variable Definition (Type + Initial Value)

Function Declaration = Identifier + Function Definition (Function Parameters and Return Value + Function Body Implementation)

Struct Declaration = Identifier + Struct Definition (Fields + Types)

- The

Identifieris the index of a declaration, used to access theDefinitionwithin the declaration. - Example: During compilation, a programming language uses the

Identifierto find the typeDefinitionof a variable for type checking.

The variable engine currently only provides variable field declaration (BaseVariableField), and extends it to two types of declarations: variable declaration (VariableDeclaration) and property declaration (Property).

- Variable Field Declaration (

BaseVariableField) = Identifier + Variable Field Definition (Type + Metadata + Initial Value) - Variable Declaration (

VariableDeclaration) = Globally Unique Identifier + Variable Definition (Type + Metadata + Initial Value + Order within Scope) - Property Declaration (

Property) = Unique within Object Identifier + Property Definition (Type + Metadata + Initial Value)

Type 🌟

Types constrain the range of variable values. In design mode, a type is also an ASTNode. Understanding types helps you reason about what a variable can store and what an expression returns.

The variable engine has built-in basic types from JSON:

StringType: stringIntegerType: integerNumberType: floating-point numberBooleanType: booleanObjectType: object, which can be drilled down intoPropertydeclarations.ArrayType: array, which can be drilled down into other types.

It also adds:

MapType: key-value pairs, where both keys and values can have type definitions.CustomType: can be custom extended by the user, such as date, time, file types, etc.

Expression

An expression takes 0 or more variables as input, processes them in a specific way, and returns a new variable. Design time only records “who it depends on” and the inferred return type—runtime handles the actual value calculation.

In design mode, an expression is an ASTNode. Modeling focuses on:

- Which variable declarations does the expression use?

- How is the expression's return type inferred?

Suppose we have an expression described in JavaScript code as ref_var + 1.

Which variable declarations does the expression use?

- The variable declaration corresponding to the

ref_varidentifier.

How is the expression's return type inferred?

- If the type of

ref_varisIntegerType, the return type ofref_var + 1isIntegerType. - If the type of

ref_varisNumberType, the return type ofref_var + 1isNumberType. - If the type of

ref_varisStringType, the return type ofref_var + 1isStringType.

The figure shows a common example: a batch processing node references the output variable of a preceding node, iterates over it, and obtains an item variable. The type of the item variable automatically changes with the type of the output variable of the preceding node.

The ASTNodeJSON for this example can be represented as:

The type inference chain is as follows:

Scope Chain

The scope chain defines which other scopes a scope can read variables from. Think of it as the whitelist for variable access. The variable engine exposes an abstract class, and product teams can implement custom scope chains as needed.

Out of the box, the engine ships with free-layout and fixed-layout scope chain implementations.

Dependency Scope

Dependency scope = the upstream scopes whose output variables the current scope can access.

You can access a scope's Dependency Scope via scope.depScopes.

Covering Scope

Covering scope = the downstream scopes that can access the current scope’s output variables.

You can access a scope's Covering Scope via scope.coverScopes.

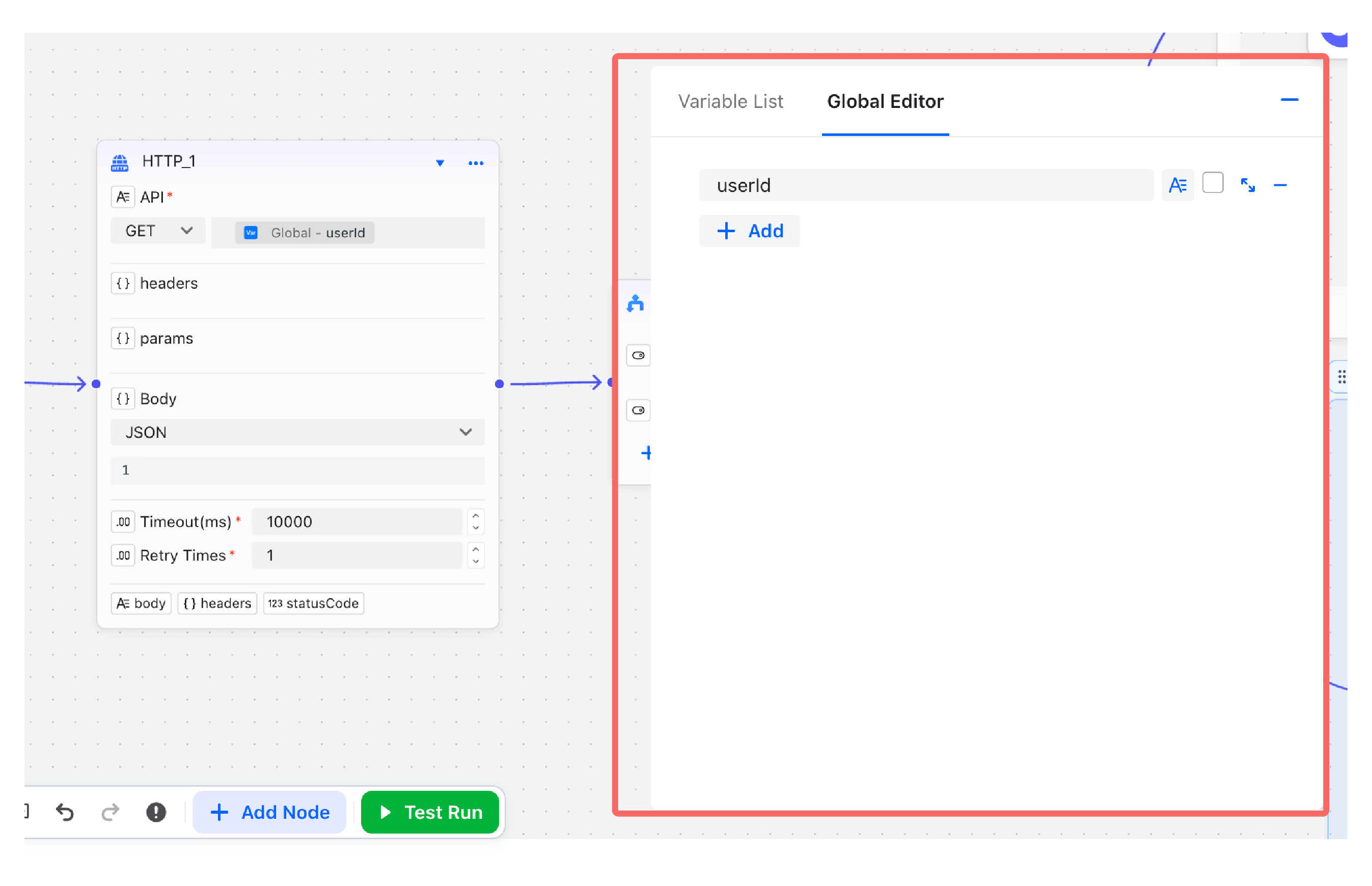

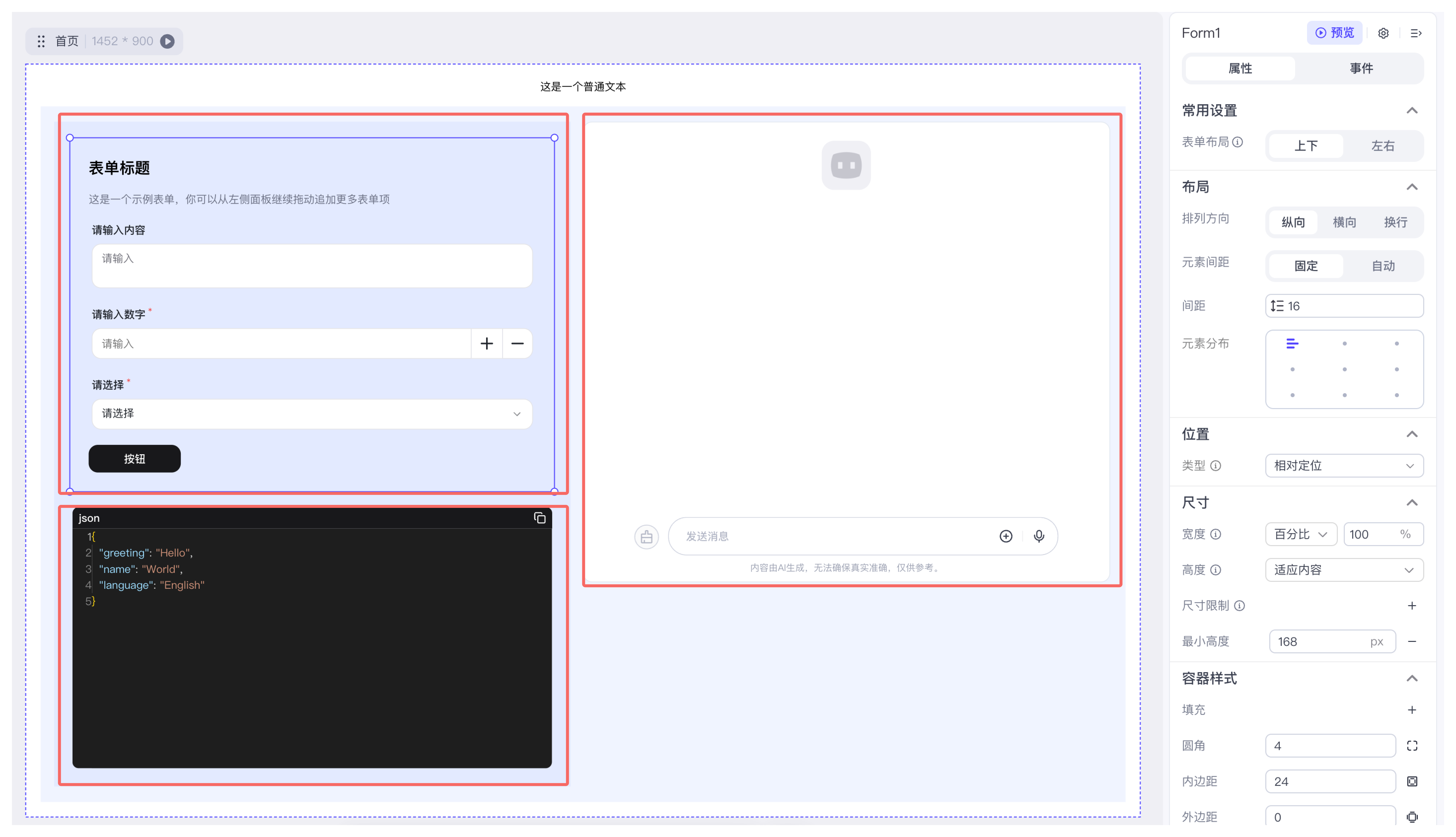

Variables in the Canvas

FlowGram defines the following special types of scopes in the canvas:

Node Scope 🌟

Also known as Node Public Scope, this scope can access the variables of the Node Scope of upstream nodes, and its output variable declarations can also be accessed by the Node Scope of downstream nodes.

The Node Scope can be set and retrieved via node.scope. Its scope chain relationship is shown in the figure below:

In the default scope logic, the output variables of a child node's Node Scope cannot be accessed by the downstream nodes of the parent node.

Node Private Scope

The output variables of a Node Private Scope can only be accessed within the current node's Node Scope and its child nodes' Node Scope. This is similar to the concept of private variables in programming languages.

The Node Private Scope can be set and retrieved via node.privateScope. Its scope chain relationship is shown in the figure below:

Global Scope

Variables in the Global Scope are readable from all node scopes and node private scopes, yet the global scope itself does not depend on any other scope. It’s ideal for configuration, constants, environment context, and other shared data.

For how to set the global scope, see Output Global Variables. Its scope chain relationship is shown in the figure below:

Overall Architecture

The variable engine follows the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) and is split into three layers according to code stability, abstraction level, and proximity to business logic:

Variable Abstraction Layer

This abstraction layer is the most stable part of the architecture. It defines the core interfaces—ASTNode, Scope, ScopeChain, and more—that upper layers extend.

Variable Implementation Layer

This layer sits closer to product requirements and evolves more often. The engine provides a set of built-in ASTNode and ScopeChain implementations, and you can register new ones or override defaults via dependency injection when your domain demands it.

Variable Material Layer

The outermost layer adopts the Facade pattern to boost usability, packaging complex capabilities into “materials” that can be reused directly.

- For the use of variable materials, see: Materials